I’m sad that I’m going to post that I’ve had my first really negative experience with a company of which I’ve been a customer for eleven years: Really Right Stuff in California. I know this doesn’t affect too many folks, but if you work with tripods and use quick releases then it might.

Spoke to their customer service folks today about an order that I placed where I was given a bait and switch: we can’t fill your order but we can sell you something for twice as much as you were going to pay. In fairness, they would have shipped it for free (a whole $10 savings on a $400 product. I don’t really care about running out of stock, but the upsell (and a crappy deal at that) and the accusation that I ordered before they could take the listing off their web site really got to me. I spoke to their customer support manager, Mark, and was told that we will not be seeing eye to eye on this, and he didn’t care that I might choose not to be their customer going forward despite eleven years of history.

So if you’re thinking about any Arca-Swiss type equipment, I’d suggest that there are alternatives, such as Kirk Enterprises, Wimberley, Fourth Generation Designs, Jobu Design, and the list goes on…

Happy Thanksgiving!

Tag: Reviews

Katie at the Gardens

While testing the Zeiss 85mm two weeks ago, I ran into Katie at the Sarah P. Duke Gardens and made a quick portrait. While I’d really need to have them side-by-side to do a more thorough comparison, it seems that the Canon 85mm f/1.2L Mk. II has far superior bokeh, but that the Zeiss might actually be a sharper lens from f/2.8 and smaller–but the Canon would definitely win at the largest apertures. Either way, the Zeiss has fantastic micro-contrast, good bokeh, and clearly has potential for portraits…so long as your subject understands that it will take a second to (manually) focus!

Like Snowing Cherry Blossoms

While I was not able to use the Zeiss 85mm lens I rented nearly as much as I had anticipated during the week that I had it, I will say that it is disappointingly soft wide-open, but sharpens up dramatically by f/2, and is wickedly sharp at f/4. The detail in the fallen cherry blossom petals is amazing!

Also, some big changes are coming as I am in the process of becoming an LLC in the state of North Carolina. More to come…

Daffodils in bloom

Last week was far busier than I had anticipated when I scheduled the rental of a Zeiss Planar T* 85mm f/1.4 ZE lens. I feel that I wasn’t really able to put the lens through its paces, mostly staying close to home due to a couple of developments that I’ll be announcing here shortly. Since I was working at home I worked with subjects at hand: loaves of bread, the cat, and our garden.

While soft wide-open at f/1.4 (to the point of being almost unusable), by f/2 this lens is razor sharp, and features the oft-fabled Zeiss micro-contrast: in-focus part of the image does seem to defy its two-dimensional nature. However, working in close quarters is where this lens struggles: the minimum focusing distance is three feet.

For this photograph of the daffodils that were in bloom in our front yard until yesterday, I had to resort to a 25mm extension tube, which presented me with the opposite of my problem: suddenly I had no choice but to be closer to my subject than I would have wished! That said, I think it works in this example. I’ll have a couple more to share after I get a spare moment to work them up.

A Better Mousetrap? A Review of the LensAlign MkII

Introduction

As long as cameras have featured autofocus, photographers have complained about its shortcomings: sometimes autofocus (AF) is dead-on, sometimes it focuses ahead of the intended target, and sometimes it focuses behind it. These flaws have been described as front-focus and back-focus, respectively. The reason for the fault in AF is found in the manufacturing process: a camera body’s AF is calibrated to a “standard” lens. However, the lenses that are produced on the assembly line are made within tolerances for deviation. With their higher resolution, DSLR’s have revealed that the tolerances in manufacturing clearly are not as strict as demanding photographers would like.

A few years ago, Michael Tapes of the eponymous Michael Tapes Design was working to create a device that photographers could use to accurately determine if and what type of focusing problems they had with their equipment. Tapes’ vision was that photographers would have proof to show the manufacturer that what they were seeing in their images was not, in fact, user error but the result of equipment. Coincidentally, just as the LensAlign Pro was coming to market, camera manufacturers provided a means to correct front-focus or rear-focus problems in-camera with Autofocus Micro-Adjustments (referred to as AFMA in this review), often buried deep in the user menu. Canon was the first to announce such a feature in its 1D Mark III body, and Nikon quickly followed suit. Note that Nikon refers to this feature as “AF Tune.”

In the fall of 2010, while reviewing a LensAlign Pro on loan from Michael Tapes Design, it was hinted that a new product was coming that would replace the less expensive but discontinued LensAlign Lite. The new unit would offer the same rear-sighting ability as the larger LensAlign Pro, it would ship flat, and it would be more cost effective for the company to produce. In total, these would make it, at least on paper, a win for customers and for the producer. And it would bear a “Mark II” designation that seems quite popular among many manufacturers at the moment.

The LensAlign MkII functions much like its larger stablemate, the LensAlign Pro, so you may wish to refer to my review of the LensAlign Pro (Part One and Part Two) before continuing. Also, if you own a LensAlign MkII, you should consult the LensAlign resources page for documentation and the ever-useful distance tool.

First a prototype and then a final production version of the LensAlign MkII was provided to me by Michael Tapes Design to prepare this review.

Design

The LensAlign MkII is essentially a scaled down LensAlign Pro that weighs in at a mere three ounces. In comparison, the LensAlign Pro is almost four times heavier at 11 ounces. One of the most exciting elements of the design of the MkII is that it shares the rear-sighting system of the LensAlign Pro.

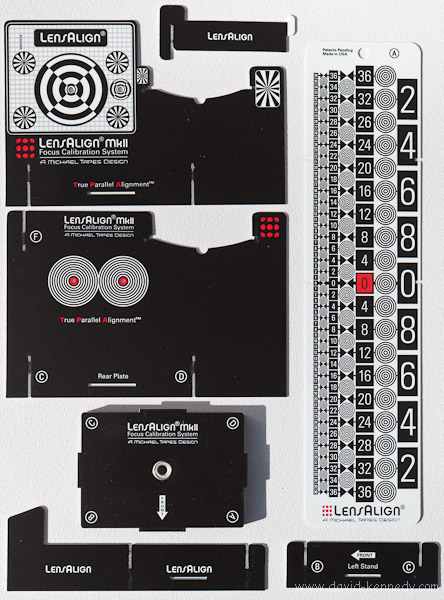

While offering the same accuracy as the Pro model, the MkII’s construction is radically different: the pieces are cut on a precision die and are assembled by the end user. The MkII ships (and can be stored) flat in seven pieces: a sturdy base made of extruded PVC with an aluminum bottom plate and quarter-inch tripod socket, a front and back plate with sights for both standard and macro lenses, and three parts that fit on the side to keep the front and back parallel all come to support the most important part of the unit: the ruler.

The components are made of thin polystyrene but they have a lot of “flex” to them; at first I feared if I didn’t put them together correctly they would crack, but they go together quite smoothly. And because the pieces can bend there’s little risk of their breaking during assembly–in fact, the ruler is designed to “bow” into place. I have taken apart and put together both the prototype and the production version multiple times without any problems.

Click through the photos below to see how the LensAlign MkII fits together:

Note that this sequence was made while I was using the prototype of the LensAlign MkII. The final production version is assembled in the same fashion.

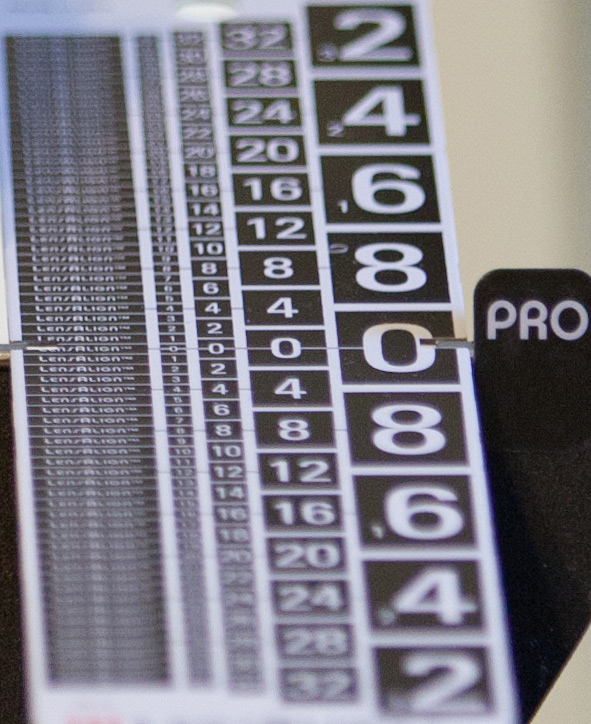

The Ruler

Since all of the other pieces come together to support the ruler, I would be remiss not to discuss it. The ruler on the MkII is an inch longer than the Pro’s, as well as half an inch wider, and double-sided with two different patterns. The first side has white numbers within black shapes, and the opposite side has black numbers within white shapes. My preference is for the white-within-black pattern, but users should try both to see which seems to be easiest for them to “read.” However, unlike the Pro, the ruler on the MkII is fixed at a 20-degree angle (Position Three on the Pro).

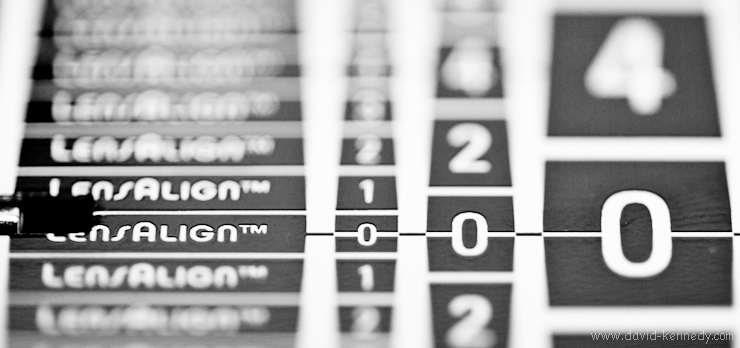

Initially I thought this might present more of a problem than it really does in practice. With the LensAlign Pro I will use the 20 degree position the most, but will occasionally switch to the 12.5 degree-angle when it seems too much of the ruler is in focus as the harsher angle limits can make the boundaries of the DOF “pop” a bit more. With the MkII the left-most row of numbers can sometimes be obscured by part of the front standard–this happens when calibrating wide angle lenses and macro lenses where the distance from sensor plane to LensAlign is two feet or less. However, the extra width of the MkII’s ruler means that there are more patterns to compare on opposite sides of the 0 Mark, so the difficulty in evaluating the smallest column of numbers is mitigated by comparing the two patterns immediately to the right, as in the photo above.

In Use

The LensAlign MkII has both a quarter-inch thread as well as four feet on the bottom for tabletop use. While it would be possible to use the MkII on a table, mounting it on a tripod offers far greater flexibility for making the face of the unit square to the camera. As discussed in the first part of my review of the LensAlign Pro, both the camera and tripod need to be positioned at a distance equal to 25 times the focal length of the lens (for instance, a 100mm lens should be calibrated from 2500mm away, or 8.2 feet). The camera and target are in alignment when the central AF sensor is aimed at the central view port on the LensAlign, with the bulls-eye perfectly centered within. For more details on the process of squaring the target to the camera, Tapes’ recent article about “Using True Parallel Alignment (sighting system) best practices” is a quick but good read.

For my testing of both the prototype and production MkII I attached Arca-Swiss style quick-release plates to make mounting on the tripod an easy affair. Another advantage of using an Arca-Swiss style quick release is that the LensAlign MkII or your camera body can slide from left-to-right within the channel of the quick-release clamp. This can make fine-tuning the position of the red AF target within the bulls-eye a snap and help avoid re-positioning a tripod when a minor adjustment is all that is necessary!

As I discussed in my review of the LensAlign Pro, there are three different ways of evaluating the autofocus performance and subsequent micro-adjustments:

- reviewing the images on the camera’s rear screen

- taking the flash card inside and reviewing the images on a computer monitor

- shooting tethered so that the images appear instantly on a computer.

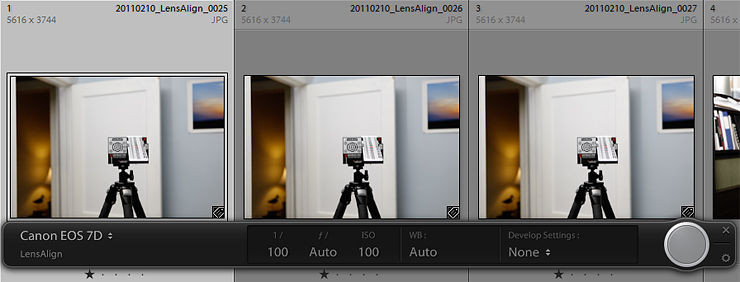

I’ve found that shooting tethered is the most effective way of working with the LensAlign MkII, but it certainly has its share of disadvantages, among them glare off of the laptop screen when working outside and power and USB cables to avoid tripping over. Simply reviewing the images on the back of the camera may be one of the “fastest” means of calibrating the focus, and it seems to work well most of the time. However, there are times when two or three micro-adjustment settings all look “pretty good” on the rear screen. In a situation like that, importing the JPEG’s (no need to shoot RAW) into Photoshop to use the emboss filter can help to determine which is the best setting.

At the moment I cannot find a way to identify AFMA settings in a photograph’s metadata (evidently Canon DPP software can provide this information on Canon cameras). It is important to be mindful that the MkII does not have an “enumerator” like the Pro (there’s no built-in visual reference for which AFMA was used or how far apart the camera and LensAlign were in a given image), but a sticky note is an easy stop-gap!

My Method

I prefer to work indoors, with the camera tethered to my computer when I’m calibrating lenses no longer in focal length than my 70-200mm zoom. I keep Adobe Lightroom open in tethered capture mode and review the JPEGs at 100% on my 24 inch monitor. A standard 16 foot tape measure will suffice for placing the camera and target at appropriate distances whenever working inside. If there’s diffuse light coming in through the window, I’ll use that. However, while I must be tripod-mounted to use the LensAlign, I prefer not to use slow shutter speeds.

So, if my shutter speed dips below 1/100 second using available light I will set up an external flash and bounce it off of the (white) ceiling in my office. Note that the flash is there to help evaluate the ruler, not the front standard, so bouncing off the ceiling is ideal as it will evenly illuminate its surface . Just be sure not to overexpose the ruler!

While I set up a flash wirelessly using an ST-E2 transmitter and a single Canon speedlite mounted on a light stand (unless I’m calibrating the 7D, in which case I will use its built-in wireless flash control), mounting a strobe in the camera hot shoe and bouncing it off the ceiling will work.

When calibrating the AF with a lens longer than 200mm I wait for good weather and set up outdoors, grabbing a 50 foot reel tape measure on my way out the door. I have tried to work tethered with a laptop outdoors, but I’ve found the glare off my laptop screen to be unacceptable. Your mileage may vary as not all screens are the same! I typically try to work off of the camera’s rear screen, but sometimes I have to make a series of images (with sequential changes in AFMA) and take the flash card inside to scrutinize the images on my computer.

I recommend recording individual cameras and lenses and the best AFMA for each combination in a spreadsheet. Include the date that you perform the adjustment! As I discussed in the second part of my LensAlign Pro review, it would behoove users to calibrate their lenses before any major shoot, and then again a month later, and once again three months to the day of the original calibration. This is because the best AFMA for a given camera and lens may change with time–although the change need not be universal. This February both my 5D Mk. II and 1D Mk. III required a change in AFMA with my 70-200mm lens–I calibrated it with a LensAlign MkII prototype over Christmas–but the setting I had found for my 7D last fall with the LensAlign Pro remained “good.”

Compared to Lens Align Pro

While it doesn’t exactly replace the LensAlign Pro, the LensAlign MkII offers the same ability to test and adjust the autofocus performance of DSLR’s as its bigger brother, for for $100 less. Of course there are differences between the two models, but how significant they are is ultimately up to the end user, but even their designer has a preference.

While speaking to me about the design of the new LensAlign, Tapes said: “Personally, I use the MkII: it’s smaller, lighter, easier.” Retail price aside, the fundamental differences between the MkII and the Pro lie in their construction, the ruler angles, the enumerator, and the Long Ruler Kits.

Construction:

The LensAlign MkII is made of thin, lightweight, and flexible polystyrene; the components are designed to be locked together and taken apart by the end user. The MkII is more portable than the LensAlign Pro, which is made of beefier extruded PVC, assembled at the factory and then laser-tested for accuracy before shipping. (It should never be taken apart since it may no longer be accurate after being reassembled.) To travel with the MkII, simply put its pieces in a rigid envelope and drop it in the bottom of a suitcase with folded pants or other clothes. I simply cannot recommend air travel with the LensAlign Pro.

Rulers & Angles:

The improved, wider ruler pattern makes up for the fixed 20 degree angle on the MkII. On the LensAlign Pro I only use the 20 degree and 12.5 degree positions any ways. Additionally, the MkII’s ruler has a matte surface whereas the Pro’s ruler is highly reflective, making the MkII easier to work with in sunny situations.

Enumerator

This might be the only thing absent on the MkII that makes me nostalgic for its predecessor. The enumerator on the LensAlign Pro can be very helpful when comparing changes to the AFMA on a computer. However, a pad of sticky notes and a pen will do the same thing, if nowhere near as elegantly.

Long Ruler Kits

An optional accessory, the Long Ruler Kit on the LensAlign Pro creates a four-foot ruler. Because the material is nowhere near as rigid, the MkII’s Long Ruler Kit will feature only a two-foot ruler. The idea behind the Long Ruler Kit is that a photographer may set up the target at a greater distance than the recommended 25 times the focal length of the lens. Tapes explains that this can be beneficial for photographers with super-telephoto lenses who often photograph their subjects from great distances and therefore would prefer to calibrate from healthy distances. Not having used one of these kits I cannot speak to their functionality, but I will say that so far I have not felt the need for one in calibrating lenses up to 1000mm in effective focal length (500mm with a 2x TC). If the idea of a four-foot ruler appeals, there is only one choice.

Conclusion

In my review of the LensAlign Pro I wrote that “The good news is that even if LensAlign is the only practical tool available, it’s a good one.” This holds true for the LensAlign MkII: no other company makes a tool that offers the accuracy of the LensAlign family of products. DataColor didn’t try very hard when they came up with the Spyder Lens Cal, and no one else has stepped up to the plate. The LensAlign Pro is a great tool, but an expensive one both for the consumer and the manufacturer. The LensAlign MkII is every bit as accurate and more gentle on consumers’ wallets. Yet, I know there are those who are going to ask whether the product is “worth” the $80 expense.

I think the LensAlign MkII a no-brainer as it helps a bag full of expensive lenses produce the absolute sharpest images they possibly can. Personally, I never knew that the 16mm end of my 16-35mm zoom could resolve the level of detail that it does now that I’ve used a LensAlign; it’s like having an entirely different–and better–lens.

In a world full of hundreds of accessories that are priced in the range of $50-$100, the LensAlign MkII might just be the best value on the shelf. Highly Recommended!

Goodbye, Mozy

All it takes to lose a customer is one e-mail

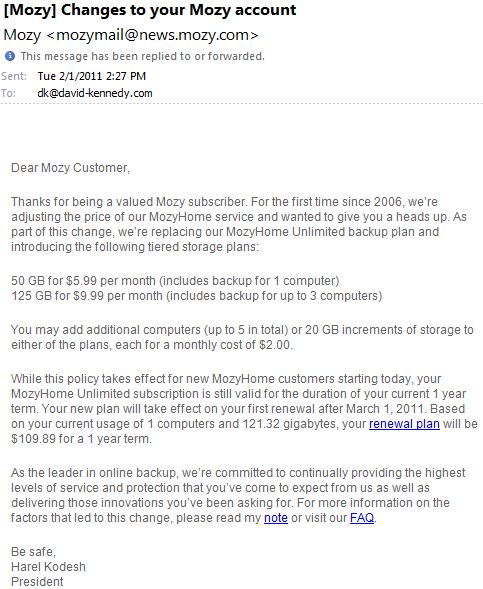

Since July 2009 I have been using Mozy’s consumer product, MozyHome, to back up my e-mail, documents, school files (past and present), Lightroom databases, music, videos, and most recently, my photographs. For a reasonable fee ($54.45 for 12 months) I could back up as much as I wanted. That ended yesterday when I received an e-mail from Mozy that the prices would be going up and the unlimited plan would be phased out in favor of a usage-based pricing schedule.

Ultimately, I was hoping to back up all of my photos to Mozy’s cloud: 516 gigabytes at present. If I had kept my account at MozyHome, and my files finally finished uploading, I would have needed their $9.99 per month ($119.88 per year) plan to get my base storage space expanded to 125 gb, and would have paid an additional $20 per month (sold in 20 gb blocks for $2 each) to cover the 391 gb of extra space I would have needed. Eventually, my annual fee for MozyHome would have become $359.88. Yikes!

To be fair, it does seem skewed that I should be able to back up 121.32 gigabytes for the same fee as someone backing up 4gb of data. However, the new fees for MozyHome don’t really address that discrepancy. The base price that includes 50gb of storage is now higher than the unlimited plan ever was–$71.88 for an annual subscription (13 months as one month is “free”). So it’s not just people who use a lot of space who are being penalized: the casual user who is only backing up his or her e-mail, word processor files, and spreadsheets is suddenly going to pay $17.43 more per year for the same service he or she had before.

As services go, MozyHome is far from terrible, but it’s not terrific either. Uploads to Mozy are slow (granted, connection speed affects this to an extent), the software is extremely buggy and difficult to change settings, and it was never clear what Mozy would do with the data it had backed up from an external hard drive if that drive was not mounted the next time it went to back-up. I’m convinced it deleted 20 gb of uploaded files simply because I had an external drive powered down, although I’d be hard pressed to prove it. Mozy was completely acceptable when it offered unlimited storage for a bargain price, but with the new pricing, I’d recommend taking a pass.

What are the alternatives?

Immediately after getting the e-mail from Mozy that their prices would be climbing, I pulled up the Web site for Carbonite and found that their annual fee for unlimited storage space is much like the Mozy of the past: $54.95. Unfortunately, Carbonite doesn’t offer an option to back up external hard drives. Unless all of your files are on the same hard drive as your operating system, Carbonite won’t copy them to the server.

Additionally, while Carbonite offers unlimited storage space, they acknowledge that they slow down the speed of uploads to their server from users who have backed up more than 200 gb of data. In short, Carbonite won’t be replacing Mozy for backing up my data in the cloud.

I was looking at other options online and one service that seems to be a contender for filling the void that Mozy left is Back Blaze. It would appear to offer unlimited data storage for $5 per month and it can back up external hard drives. I may give it a trial run, but anyone who has experience with Back Blaze or any other the other online back up providers is encouraged to share their experiences in the comments below!

So what to do?

At the moment I’m going to depend on the two back up hard drives I rotate off-site, in addition to the hard drive I’ve recently set up as Networked Attached Storage (NAS) via a PogoPlug. While it isn’t the fastest NAS solution, the PogoPlug does have another trick up its sleeve: I can access the files from anywhere with Internet access!

I’ll have a tutorial of how I use PogoPlug, Microsoft SyncToy, and the Windows 7 Task Scheduler to keep my files backed-up across the network.

Back-focused? Front-focused? A Solution: A Review of the LensAlign Pro in Two Parts

Part Two:

This is a continuation of my two-part review of the LensAlign Pro. You may wish to refer to part one before continuing!

Final Preparation for Testing

So you’re set: you’ve calculated the distance you need, set up your camera on a tripod (and possibly placed LensAlign on another tripod or a sturdy table), and you’ve confirmed LensAlign is square to the camera/lens in Live View or by zooming into a review image. What now? Close the Sight Gate so that your camera cannot focus on the rear standard of the LensAlign. Set the ruler to the third position (20 degrees) for initial testing. Ensure that you are set to you lens’ largest aperture; if you’re calibrating a 50mm f/1.4 lens, you need to be shooting at f/1.4. Expose properly for your lighting situation–you do not want overexpose the ruler!

A Brief Note on Technique

Even though you’ll be working on a tripod at reasonably fast shutter speeds, I find it can help to set the camera in mirror lock-up with a two-second countdown timer when working with 70-200mm lenses and smaller. For larger lenses with tripod collars I switch out the ball head for a gimbal-style head and employ the long-lens techniques I’ve learned from Arthur Morris: I lock down the lens with my arm hooked around the head and down onto the lens while applying pressure to the top of the camera with my forehead as I look through the viewfinder.

To make the test image you will manually rack the focus so it’s blurred, and then have the camera autofocus on the center of the target: you want the camera to have to “work” to get the image in focus. Make an image and review it.

For now, I’m going to assume you are using a prime lens. Check the LensAlign Distance Tool for a calculation of how much DOF should extend in front and back of the focus target (0 mark on the ruler). For this example I will assume the calculation is close to 50-50. The first thing you need to determine when looking at the review image is where the DOF begins and ends, bearing in mind that you want the DOF to split evenly on the top and bottom halves of the ruler.

When you’re reading the ruler, look for noticeable crispness in the numbers, starting with the large ones. Is the “8” sharp on both the top and bottom? How about the “6” or the “4?” Sometimes, the larger numbers are a bit confusing, but as your eye scans the ruler, look at the columns of smaller numbers and ask yourself what is the last number you can read clearly on the top of the ruler, and then look and compare that to the corresponding number on the bottom of the ruler.

If you think the numbers on the ruler are hard to read, or that it is difficult to tell where the boundaries of the DOF lie, try adjusting the ruler angle. Rarely do I use the first (45 degrees) or second (30 degrees) position, but I frequently will make the angle harsher and go to the fourth position (12.5 degrees) to camera. Especially for longer lenses, a shallower angle really helps to clearly spot the boundaries of the DOF. Note that for those who want a longer ruler to judge autofocus on long lenses from greater distances than the proscribed eight feet per 100mm of focal length, the LensAlign Long Ruler Kit gives the Pro a larger focus target and a four-foot long ruler.

If the DOF is pushed to the top half of the ruler, your camera is back-focusing, and you will need to use a negative AFMA correction to “pull” the DOF back down the ruler. If the DOF has mostly sunk to the bottom half of the ruler, your camera is front-focusing, and you will need to use a positive AFMA correction to “push” the DOF up the ruler. If the DOF falls perfectly on both sides of the “0” mark of the ruler, then congratulations, you’re done with this lens, and can move on to the next!

Correcting Front or Back-Focus

Begin with a simple adjustment: one increment in the direction needed to correct the focus. After setting the AFMA in the camera menu, turn the focus ring by hand so that the camera will have to re-acquire focus, and make a new test frame. (If you wish, you may alter the enumerator so that the AFMA is recorded in the frame.) In my experience every lens/camera is different, and responds differently to AFMA corrections. Sometimes, a +1 adjustment appears to have no effect in pushing the DOF up the ruler to correct front-focus, and it may take more drastic increments (+5, +10) to get into the ballpark. Other times, the change is dramatic and +1 or +2 moves the DOF significantly. Start small, and work your way up (or down) the AFMA scale until you find the right setting for your lens.

The following video is an example of one lens/camera combination where changes in AFMA were very, very slight, and it wasn’t until -18 that I found a good balance of the DOF on both sides of the ruler. Here you will see it step-by-step, but in practice, I first attempted -1, then -2, and -5. When no change was apparent, I jumped to -10, and then to -15. From there I went step-by-step until hitting -18, the “sweet spot.”

LensAlign Pro Demonstration from David Kennedy on Vimeo.

At 0 AFMA, the back-focus is quite significant, so you will only gradually see the numbers on the bottom half of the ruler come into focus in balance with the focus on the top half of the ruler (achieved at -18 AFMA).

What about zoom lenses?

Put simply, calibrating zoom lenses is a balancing act. Most cameras provide only one AFMA per lens (Olympus seems to be the exception to the rule), but zoom lenses comprise a great number of focal lengths! Test the focus performance of the lens at some of its designated focal lengths marked on the barrel; on a 16-35mm lens, you might test at 16mm, 24mm, and 35mm. Unfortunately, the AFMA that is ideal for one “end” of the zoom range might not be as good for the other. In such circumstances, you will have to make a choice of which one is more important to you for that lens.

For instance, I have both a 16-35mm lens and a 24-70mm lens, and there is obvious overlap between the two. When calibrating my 16-35mm, I found that the ideal AFMA for the 16mm setting resulted in severe front-focusing at 35mm. However, my 24-70mm lens works quite well throughout its zoom range, so I decided to keep the setting on my 16-35mm to make the widest end perform the best, knowing that if I want to zoom in longer than 24mm I will change lenses.

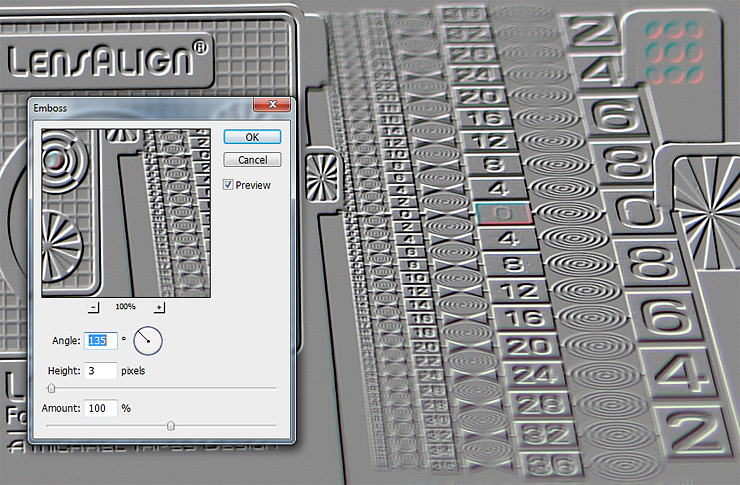

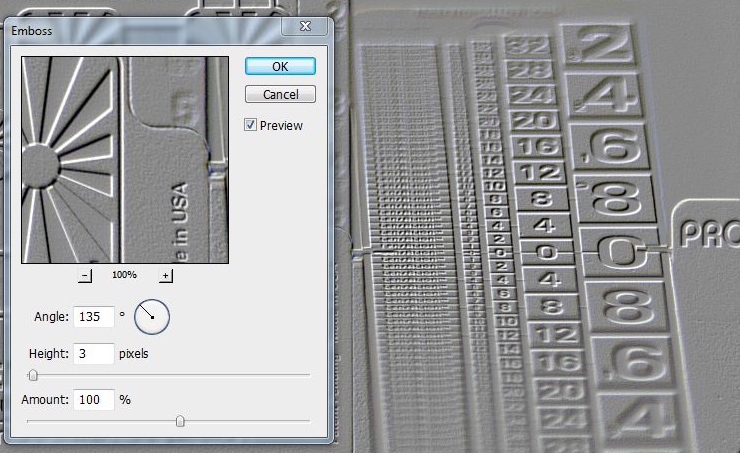

Using the Emboss Filter

Whether reviewing the images on the back of the camera or on a computer, there are times when it is less obvious which AFMA correction offers the very best balance of DOF on both sides of the ruler. When trying to choose between two or three AFMA settings, try loading the photos into Adobe Photoshop and applying the emboss filter with an angle of 135 degrees, a height of 3, at an amount of 100%. The “relief” image you will create can help identify the exact edges of the DOF.

How long does calibration last?

For a while I believed that AFMA is something you could “set and forget.” There are exceptions to this, of course: every time you send in a camera or lens to the manufacturer for service you should put it back on the test bench with the LensAlign. Do not be fooled if the AFMA changes are still in the camera you just had returned from the factory: test and verify for yourself that they still work well. This happened to me in the fall of 2010 when I sent in my Canon 5D Mk. II for a “clean and check” and it was noted that autofocus had been re-calibrated at the factory. The body came back wiped but with AFMA changes still registered, but they were no longer ideal adjustments: I had to calibrate my lenses all over again.

There are times when the ideal AFMA setting may shift for a host of reasons that are beyond a user’s control. It would seem to me that testing AF performance on a quarterly basis is an easy rule of thumb that most users can follow, but for professionals a more proactive approach might be needed.

In talking to Michael Tapes, he offered the following advice: calibrate using LensAlign before any big shoot (travel, a high-paying portrait shoot, etc.) and then again a month later. Wait two months from that day and confirm if the AFMA is still working for your camera/lens combination.

Conclusion

The LensAlign family is products is, for the moment, the only game in town for accurate autofocus micro-adjustment calibration. None of the major camera manufacturers have a consumer product to use with their micro-adjustment-capable cameras, and it wouldn’t appear that any of them intend to fill the void that they created when they released a feature with no corresponding tool. Yes, Datacolor is attempting to compete with the Spyder Lens Cal, but their product has no means of squaring the target to the camera, making it pretty much useless. It simply doesn’t provide the accuracy or repeatability that you find in Michael Tapes’ LensAlign.

The good news is that even if LensAlign is the only practical tool available, it’s a good one. The LensAlign Pro is a very sturdy and capable product: squaring it to the camera is fast, the ruler can be locked into several different angles so you can adjust the experience to your preference, and the handy enumerator makes visual “note taking” of distances and AFMA settings a snap. At $180 the LensAlign Pro is not an inexpensive product, but this is not another injection-molded plastic wonder: each one is assembled by hand individually in the United States and then laser-tested for accuracy.

The disadvantage of the LensAlign Pro is that its sturdiness and size means that it doesn’t travel well: it’s a unit that stays home or can be packed in a car, but air travel is almost entirely out of the question.

Michael Tapes clearly recognized that retail price was an issue for some people, and the size of the LensAlign Pro meant that shipping internationally was a problem for the company, so he created a new stablemate, the LensAlign MKII. The new product sells for $80 and offers much of the same functionality as the LensAlign Pro in addition to packing flat both for shipping and travel. A review of the MKII will be posted here before the end of the month, but in short new product is essentially a scaled-down, less expensive LensAlign Pro. There are some advantages to the bigger brother, however, and as Michael Tapes explained over the phone people will buy the LensAlign Pro if: “They want the enumerator, they want the ruler angles, or they want the 4-foot ruler.”

The bottom line is that if you are serious about getting the sharpest images from your micro-adjustment capable camera, you cannot go wrong with the LensAlign Pro. Highly recommended!

On a fall day – Part Three

Parting Thoughts on the 70-200mm f/2.8L IS Mark II lens

When I first received the new 70-200mm lens from Canon Professional Services, I was instantly reminded why I sold my old 70-200mm f/2.8 (non-IS) a few years ago: it’s big and it’s heavy. But it lets in a lot of light, and you can achieve very nice, selective focus with it. I didn’t have an opportunity to make any portraits with it, which is too bad because I think it would be an excellent lens for that application. I did take it out on the street, but I was very conscious of walking with an enormous white monstrosity: subtlety is not an option with this lens.

A Worthwhile Upgrade?

The image quality is remarkably high (although I wouldn’t consider its resolution to be any greater than it’s f/4 stable-mate, and while the image stabilization is improved over the previous version, I did not think it any better than the aforementioned 70-200mm f/4L IS. That said, this is the first zoom lens that I would consider using with the 2x teleconverter on a regular basis.

If you currently own the older IS version of this lens, you might wonder if it’s worth the upgrade. I would offer that I believe the image stabilization is certainly better, but if you shoot sports, that might not matter to you at all. The image quality is higher, and will enable you to use the 2x teleconverter freely. If neither of these features interest you, then you can probably pass on this lens and wait for something “better.”

On a fall day – Part Two

Experimenting with the 2X Teleconverter

Over the weekend, Arthur Morris posted on his blog that he was experimenting with the new 70-200mm f/2.8L IS Mk. II lens with Canon’s 2x II teleconverter, which turns the lens into a 140-400mm f/5.6 lens. When using this combination, the short end should be avoided with this combination because 140mm is encompassed by the lens’ natural zoom range. I was intrigued by Artie’s post because he was so excited by the image quality he was getting with this combination, and since I had such a lens on hand from Canon Professional Services, I thought I’d go out and give it a try, and I was impressed: it is sharp, and it works well!

Now, I could do this with my 70-200mm f/4L IS lens, but then I’d be working at f/8, and would have to stop down to f/11 to overcome the vignetting that is inherent to working with teleconverters, so I usually only work with the 1.4x TC. The bottom line is that this is a surprisingly useful application for the new zoom lens, especially for nature photographers, but for most other forms of photography as well. I certainly wouldn’t argue it’s “as good” as having a 300mm prime and a 400mm prime lens, but not everyone carries those two lenses with them daily!

On a fall day