Tag: Reviews

Sharing a moment on the bridge

An old lens updated…and enlarged?

Lens envy is something every photographer experiences, and sometimes it’s made worse when a lens you love is replaced with a newer, more expensive version. I suppose this is what people who have iPhone’s go through every June.

About five years ago I purchased a Canon 24mm f/3.5L TS-E lens for its ability to control perspective…that is, I wanted to get a view looking “up” at a building without the lines converging. And it was a small, albeit dense, lens, so it was pretty easy to slip into a camera bag and take it along just in case a landscape or architectural situation demanded it. But it had its flaws, chief among them being that the tilt (also known as swing) movement comes from the factory 90 degrees from the shift (rise and fall) movement. That means that if you want to use shift to get a higher perspective, but also tilt the lens downward, then you’re out of luck unless you send the lens in to Canon to be altered so that they’re on the same plane.

Back-focused? Front-focused? A Solution: A Review of the LensAlign Pro in Two Parts

Part One: Overview and Setup

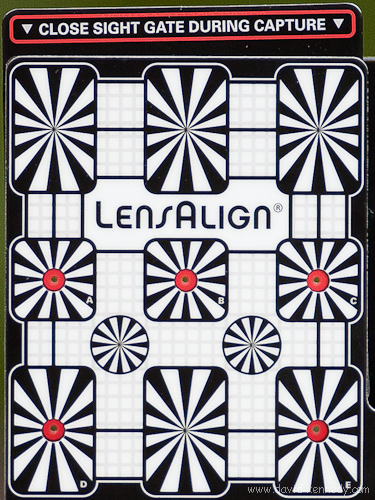

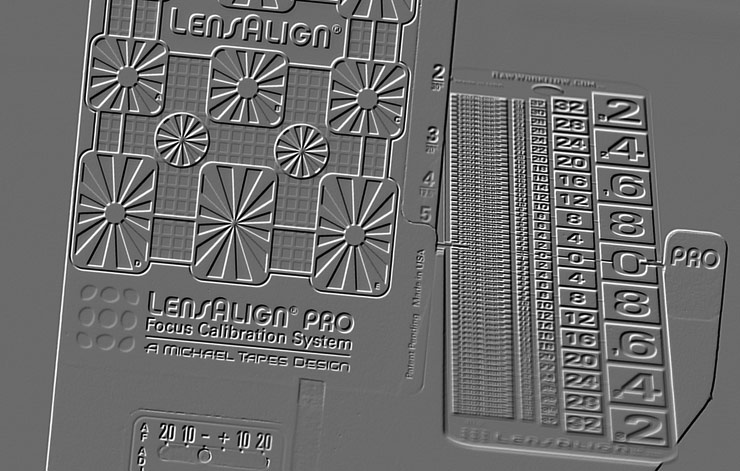

LensAlign Pro

Earlier this month, Michael Tapes, president of RawWorkflow, e-mailed me because he saw my mention of Datacolor’s product, aimed to complete with his LensAlign, the Spyder LensCal. He also referenced my account of working briefly with one of his company’s LensAlign Pro units this summer. Michael then offered to have a review copy of the LensAlign Pro sent to me for a closer look at this useful, if somewhat expensive, tool for properly calibrating the autofocus performance of a camera and lens.

While many manufacturers, including Canon, Nikon, Sony, and Olympus, now provide a means for end-users to calibrate the autofocus performance their prosumer and professional cameras via “autofocus microadjustment” (AFMA), none of them offered a tool for making these changes in a meaningful way.

LensAlign, then, is a platform for measuring the focus accuracy of a camera/lens combination. One takes this information and then, if necessary, change the AFMA to shift the depth-of-field (DOF) so that it straddles the “0” mark on the LensAlign ruler. I will explain the overall functionality (although I do not intend to re-create the wheel–the LensAlign manual is on the company’s resources page) and consider why one would purchase such a product.

Debunking the 1:2 Depth of Field Myth

One of my initial concerns about this process is that I’ve heard for years–from anecdotes in photography books to some of my professors in graduate school–that depth of field is split in a 1:2 ratio around the point of focus. That is, 1/3 of the DOF resides in front of where one focuses and the remaining 2/3’s lies behind it. But LensAlign is designed to make the DOF 1:1 in front and back of the focus mark, which seemed to go against the grain. Someone has to be wrong!

In researching this, I found a page of “Common photography myths,” and sure enough, number 14 was that DOF was 1/3 in front and 2/3 in back. Essentially, DOF is mostly 1:1 front to back. However, as magnification is decreased (distance from subject becomes greater, i.e. farther back in the frame), DOF slowly grows to become closer to the 1:2 ratio of lore. Then, as one focuses more towards infinity, the ratio becomes 1:∞, and hyperfocal distance is achieved.

The DOF ratio is not always 1:1, hence my saying “mostly.” For example, with wide-angle lenses, particularly at close distances, the split becomes 40% in front and 60% behind the focus mark. If you want to know more about how depth of field is calculated, you can find the formula here, and a list of known values for the circle of confusion of several camera models can be found here.

All this aside, I suppose if one desires a 1:2 ratio for depth of field, one can use LensAlign to shift it to one’s liking, but it is a choice to alter the way that things are designed to work for one’s creative needs, it is not “the way it should be.”

Inside the Box & Initial Setup

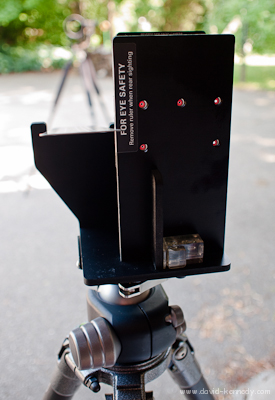

Upon opening up the white clam-shell box, one finds the main unit, and a postcard detailing how to set up the following components: its metal ruler, the “sight gate,” a magnetic on an adhesive strip for the “sight gate,” and four small, cylindrical magnets for use with the LensAlign’s “enumerator.”

The body of the LensAlign Pro is made of four pieces of extruded sheets of PVC that have been cut with a router. Two vertical pieces are parallel to one another–the front containing a the focusing target that also holds the “0” mark of the LensAlign ruler. The rear vertical piece contains the bulls-eyes for making the unit square to the camera position. A third piece is perpendicular to the other two, and keeps them straight. All three are screwed into a square of PVC with a 1/4″ tripod thread in the center. To keep the two focusing pieces parallel to one another, and to prevent them from bending in transit, a length of poster tube is packed between them for shipment. Keep this piece in the event you ever want to travel with LensAlign Pro!

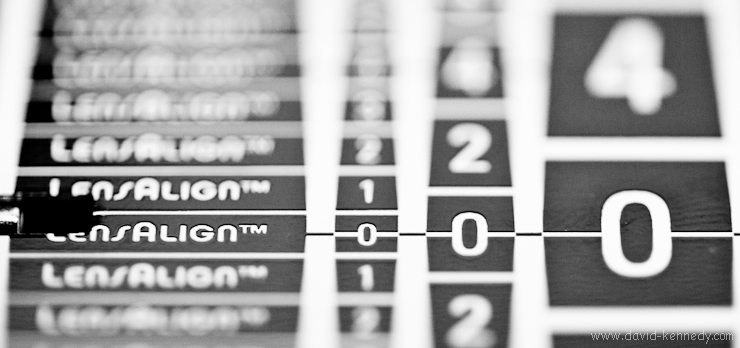

The ruler is a 9.5″ strip of metal, and it is how one gauges the focus calibration of their camera/lens. Every other part of LensAlign is designed to work to support this ruler. So, while in the initial setup the user concentrates on everything except the ruler, during the actual measurement stage, the ruler will be all that matters.

The sight gate is a plastic card that will slide up and down to open and close the bulls-eye’s in the front of the LensAlign. However, to make it slide, one has to adhere a magnetic strip on the back of it (it’s a little odd that the user has to do this, and I assume it has something to do with labor costs to produce LensAlign, but it is a trivial matter to do it one’s self).

Once set up, the main unit could be used on a tabletop, but a 1/4 inch thread allows it to be mounted onto a tripod. One could mount the unit onto a light stand, but for reasons explained later, it is better to have the unit on a tripod head that allows movements, such as a ball head.

The enumerator and the ruler

The ruler has various positions that it can be set to (and held in place by magnets). They range from virtually parallel to the imaging plane to almost perpendicular. However, the LensAlign documentation recommends beginning with the ruler at the third position, and my experience seems to confirm that this is usually a good starting point.

That said, I tend to use the “flatter” ruler positions, 4 and 5, just as frequently as I do position 3. The greater the distance between the camera and the LensAlign, the flatter the ruler should be, as it makes it easier to distinguish the boundaries of the DOF.

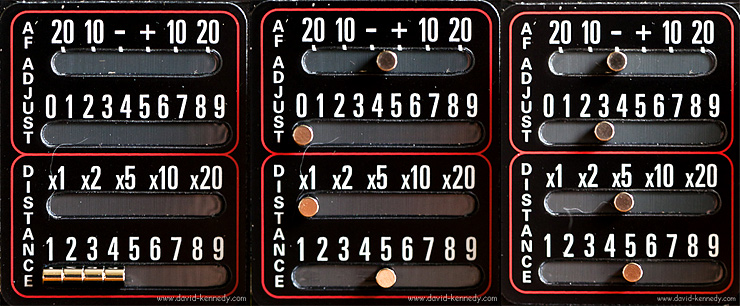

The enumerator is not essential for the operation of the LensAlign, but it is a handy feature if one makes a series of images at different AFMA’s and reviews them later on a computer screen, as it provides a visual record of the AFMA setting.

Working with Test Photos

That is to say that there are at least three ways to work with the test photos of the LensAlign: review them immediately on the rear LCD screen and tweak the AFMA on the spot, shoot tethered to a computer and review the pictures in the field with the camera, or make the initial (neutral AFMA) test picture and review it in-camera, and then make a series of incremental AFMA changes and download all of the images to a computer for review.

The advantage of the first option is that it might be a little faster, but the latter two choices tend to be more accurate as they involve larger computer monitors for viewing the test pictures. Hence, if one chooses to review the images on the computer, the enumerator provides an easy reference for the settings used.

Personally, I have tried all three options, and find that they all have their time and place. I don’t have a setup like Joe McNally, but if I did I would shoot tethered for everything. (To make his setup, one needs a tripod, a Manfrotto dual-head “bar” to mount on top of it, a laptop table to mount on one side of the bar, and a tripod head of some kind for the other.) Since I don’t have those parts, I chose to tether only when I was indoors. Outdoors, I find that I can roughly eyeball whether I’m front or back-focused on the rear LCD of the camera. Once I believe that I have found the proper AFMA for the lens I’m using, I’ll bring it inside and check it on my computer monitor.

A Word About Placement

Before one can make a test image to determine any front or back-focus, one must first place the camera and LensAlign on separate platforms, space them, and make them square to one another.

It really helps to have the LensAlign either indoors with indirect lighting, but I suppose if you’re feeling motivated, you could set up flashes to illuminate it. When using it outdoors, be sure to place the unit in shade, or use it on an overcast day. The ruler is extremely reflective, and direct sunlight turns it into a blinding mirror. You want the light falling on the ruler to be even for easy-reading!

The online distance tool helps to determine how far apart the camera should be from the LensAlign, as well as how “deep” the DOF should be with a given focal length and sensor size. This distance can also be calculated manually by multiplying the focal length by 25. So, for a 400mm lens, one would need to be 10,000mm from the target, or 32.8 feet. TIP: A 50-foot reel measuring tape will be very helpful for this step if you own telephoto lenses!

I have also tried calibrating lenses at their minimum focusing distance (MFD) instead of the recommended distance. In a way, it’s easier because one just moves back as far as one needs in order to get LensAlign in focus. Additionally, the target will be larger in the frame the closer one is to it, making the markings on the ruler easier to read. In fact, in my first draft of this review, I suggested that MFD might be all you need. But then I was proven wrong!

My advice for telephoto lenses 400mm and longer would be to first make an adjustment for the MFD, and then back up to the suggested distance to confirm the adjustment. I recently calibrated a 500mm f/4L with my 1D Mark III and discovered that the adjustment made to counteract back-focus at MFD was too extreme, and actually caused front-focus when set at 41 feet from the target.

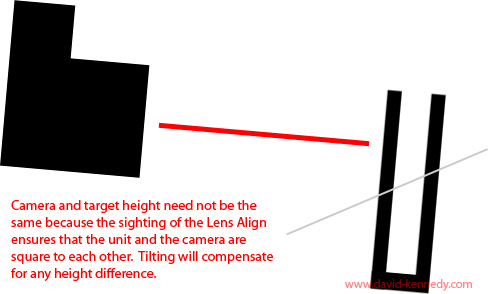

Aligning LensAlign

The first step you should take is use your tripod head (you have to be tripod-mounted) to position the camera at the LensAlign. Aim the center focusing point (the most accurate of the focusing points, irrespective of camera brand or model) at the center bulls-eye of LensAlign. Then, run behind the LensAlign, and looking through the “peep hole” through the center bulls-eye, lock it in position so that you are looking through the center of the lens. Often, you can see light coming in through the viewfinder of the camera through the middle of the lens, which can help to make it just right.Return to the camera, and switch on Live View (or take a picture and review it on the LCD) and zoom in to see if the center bulls-eye is truly centered in its viewing port.

An aside:To my knowledge, every camera that has the ability to make AFMA changes also has live view. However, the LensAlign is helpful even with cameras that do not have this feature, as it can confirm whether or not there is a focus problem with a given lens. If there is a problem, the user can take the data and decide whether the front or back-focus exhibited warrants sending the camera and lens to the manufacturer to be professionally calibrated.

While the LensAlign manual does explain how to make the unit square to a camera, I have found that it helps to pay attention to more than the center bulls-eye, but to consider all of them. Especially at shorter distances and wider focal lengths, the other four bulls-eyes will not be centered in their viewing ports, but making sure that they are symmetrical on opposite sides of the center bulls-eye ensures that the plane of the LensAlign is parallel to the camera’s sensor plane.

Corrections and A note about Keeping Things Level

In the original version of this review, incorrectly stated that the body of the LensAlign is made from black masonite. While it has that apperance, it is actually made from PVC.

Additionally, in the original posting I emphasized that keeping both the camera and LensAlign level, by means of a hot shoe bubble level or otherwise, would be a good idea.

After speaking to Michael Tapes directly, I stand by thinking that it’s helpful to keep things level, but agree that it is not essential for the operation of LensAlign. Hence, I have removed it from the section about aligning the focus target to the camera lens. In fact, he told me that the absence of a level “wasn’t a casual omission.” He believes that adding a level the product would make it appear to the user that being level was part of making the camera and focus target square, when it is not, in fact, a necessary step.

A level camera and a level focusing target will not change the DOF–it’s a constant. Camera lenses do not draw rectangular images, but circular ones, so how the camera is rotated on the lens doesn’t change the DOF. However, I find that leveling both helps in reviewing the images from LensAlign, because my beleaguered brain doesn’t like to look at picture of a ruler that is skewed at a 5° angle.

For me, I find the lack of a level to be my lone frustration with the product. I say this because it is downright annoying to constantly walk back and forth between the camera and the LensAlign while trying to remember to take the level with me each time. When I walked 41 feet out to the 500mm lens that I was trying to make square to the focus target, and realized that the level was still sitting on the back of the LensAlign, I really started grousing!

But to reiterate: it is not necessary to do this extra step of leveling the two devices, I just prefer to work this way, and I think many photographers who will take the time to change the AFMA in their cameras will feel the same as I do that looking at a level measurement tool is easier than looking at one that is tilted, even if the data is the same.

Read part two of the review now!

Sometimes, it’s the little things…

There’s one thing that I use with all of my computers (laptop, desktop, netbook, and even my iPod Touch) that makes the task of moving files around so painless that I’m not sure how I ever got by without it. I’ve been using it for almost two years, and I continued to be baffled by how uncommon it is to find other users. I’m talking, of course, about USB flash drives Dropbox. It’s a way of having your files on your computer and in the Cloud all at the same time.

Read More after the jump!

Continue reading “Sometimes, it’s the little things…”

Past its Prime?

A Review of the Canon 135mm f/2L Lens

Preamble

The Canon 135mm f/2L lens is one of the more highly regarded lenses. Together with the 35mm f/1.4L and the 85mm f/1.2L II lenses, it is popular among photographers for the special “look” that it gives images, and in a way, deservedly so. The subject is easily isolated from the rest of the frame, making the challenge more of creating a pleasing composition than of worrying if the image will be too “cluttered.” However, my experience with the lens for a week, courtesy of Canon Professional Services, has left me wondering if the reputation that the lens built for itself is as deserving in the age of 21+ megapixel camera bodies and circular aperture blades. While it surely is effective wide open, the lens appears not to be as sharp as it could be in all circumstances, and stopping the lens down reveals the potential for distracting backgrounds, as my comparison between this lens and the 70-200mm f/4L IS zoom lens will reveal later in the review.

Looking its best

Without question, wide open the lens creates a very compelling and desirable effect for its focal length. The advantage of telephoto compression means that the foreground can be easily distinguished from its background, and the lens’ wide maximum aperture (f/2) helps to obliterate what’s left of said background. With such a fast telephoto lens, foliage only a few feet behind a subject can be turned into an almost seamless background of solid color. Furthermore, the glass is cut in such a way that some subjects seem to literally pop out of their two-dimensional planes, giving them very “3d,” almost Zeiss-like appearances. Indeed, the color and the contrast that come from this lens is impressive.

Below are a few examples that illustrate some of the very best traits of this lens:

In this example, the background flowers are no more than inches behind the central subject (with the yellow flowers about two feet behind). And at 100%, the sharpness is quite stunning despite being made wide open. I must note, however, that images made of subjects physically closer to the lens (particularly in the 3-5 foot range) appear sharper than do those made in the 10 foot to infinity range. However, as I do not have any lens AF Micro-Adjustment equipment on hand, I can say only that this is a perception, but I cannot say an incurable one–AF Micro-Adjustment very likely would address this issue.

More after the jump!

The impeded stream…

For the past week I’ve been working with a Canon 135mm f/2L lens from Canon Professional Services. I’ll be publishing my thoughts on this lens soon, but until then, a bit of a “teaser” from last evening.

Two views from the ferry

Together with Elizabeth’s family I spent a week in the Outer Banks of North Carolina in mid-August. While I had high hopes of making landscapes of the coastline and the Cape Hatteras Light Station, it didn’t quite work out. Combining a family vacation with photography is clearly an art that my parents somehow perfected, but I will have to learn to do myself.

That said, I was able to do a fair number of pictorials, particularly on the car ferry that took us from Hatteras to the island of Ocracoke. I had rented a Zeiss Distagon T* 35mm f/2 ZE (Canon-mount) lens for this trip, and while I didn’t use it as much as I had hoped, I did make enough to get a general impression of how the lens handles and renders its subjects on the sensor. What I was looking for in my photographs was the “Zeiss look,” defined by strong micro-contrast and subjects that want to pop out of the frame (read: three-dimensional). I’m not convinced that I found this look in every frame that I made with this lens, but it was there in several of them. Having experimented with the Canon 35mm f/1.4L a few months ago, I was curious how my experience would differ.

I will say that the Zeiss lens is demonstrably sharper than the 35mm f/1.4L–the edges hold together better, and even the center is much sharper. I believe the online rumors that the 35mm f/1.4 is due for replacement and that Canon surely is working on a successor; after all, the 24mm was re-staged with a Mark II designation not that long ago, and with the increase in resolution from the cameras coming down the pike, the 35mm is going to demonstrate too well that it is an older lens design. That said, the “effect” that these lenses provide is similar–strong vignetting so that the subject of the photo really “pops” when shot wide-open.

While I am still in the process of going through my images from the trip, as well as evaluating two lenses from Canon (the 135mm f/2L and the 14mm f/2.8L II), I would tentatively say that I give the nod to the Zeiss lens over the Canon 35mm because while they do produce similar effects, the sharpness and control of chromatic aberration with the Zeiss is overwhelming to the eyes. But, the Canon lens has autofocus (the Zeiss being manual focus only) and is a full stop faster, so anyone trying to decide between the two should keep those details in mind.

More to come.

Horicon after LensAlign and Focus Tweaks

A Brief History of “Back-focus”

Last weekend I was at Horicon National Wildlife Refuge and experienced some focus problems with my Canon 7D heretofore non-existent, or so I thought. Upon reviewing photographs from the 7D from the past several months, I noticed that none of them were actually as sharp as they could have been. I attributed the softness to the lack of acutance in the files, and while I continue to believe that is an inherent property of cramming 18 megapixels into an APS-C format sensor, there was a real problem in play.

I didn’t want to believe that it could be a question of the camera “back-focusing” (or front-focusing) because I’ve grown to distrust people’s claims that their camera, and not their own inabilities, are to blame for their out-of-focus photographs. I don’t remember these claims from the film days. Perhaps I was just oblivious to the complaints, but I tend to believe that the instant feedback of the digital camera is partly to blame for the knee-jerk reaction that anything wrong with the pictures must be camera, not operator, error.

I will not mince words: ever since the Canon 10D and the Nikon D70, there’s been a lot of bitching and moaning in online forums about back-focused images, and I did not believe them. At all. Until now.

Now, I will argue that there is definitely operator error to blame in most many cases of complaints about back-focusing. Last weekend I was convinced that I must have chosen the wrong focus point or didn’t have the AF locked by holding in the rear button–some prefer AF to only be activated by using the back button, I prefer AF to only be turned off if I hold in the back–and allowed AI Servo (Continuous AF for Nikonians) to screw up the focus. To confirm my assumption, the next day I took test photographs in the garden around my parents house in Racine, Wis. and was shocked to discover that none of them were sharp. Sure, the wind was to blame in a couple cases, but even when conditions were perfectly still the results were poor, so I rented a LensAlign from Lensrentals.com to investigate whether front or back-focus was to blame.

And what did I find after I unpacked and set up the LensAlign? The 7D and the 5D Mark II both back-focused with the 400mm DO IS lens. Well, there goes the neighborhood. And a lot of preconceived ideas, with it.

Post continues after the jump! Continue reading “Horicon after LensAlign and Focus Tweaks”

Derelict a la Lensbaby

On Saturday evening my dad and I went down to Pugh Marina in hopes of catching a moonrise. But as we got to the lake, we saw a heavy haze on the horizon above Lake Michigan, and the hopes for a moonrise dimmed. However, I took advantage of the fleeting golden-hour light to walk into a normally gated area at the marina that used to be chock full of derelict boats. Evidently, the marina has been getting rid of them, because the gate was wide open (it actually has been for days–I just finally took the initiative to walk over to it) and only three remain. I’m 99% certain that if you dropped this boat into the lake it would just sink.

In my last post about the Lensbaby I was hesitant to recommend it. I will say that, after using the Lensbaby Composer some more, it does have a learning curve and I think the hardest thing to know is when to use which aperture with this lens. This is especially true as you have to manually insert and remove the aperture “blades” (washers), and since it’s a rental I don’t want to risk carrying them around and losing them! What I am slowly discovering is that I like this lens with a little more depth of field than it has wide open or even at “f/2.8.” The image above was captured at f/4, and I think I may try f/5.6 in my next experiment. Food for thought.